In Japan, a teacher

(sensei) is conscious of the expectations of his work that are predominant in the public. He is not only expected to assure the children’s right to receive education, but also to have to fulfil a huge scope of duties holding a wider role and responsibility than in the West.

Japanese teachers work very hard and often feel overworked because of an enormous number of lessons a week and the additional tasks inside and outside school. Some even fear

“karoshi”, meaning death from overwork. In 1993, the time of classroom teaching was 16.8 hours for high-school teachers, 19.7 hours for middle-school teachers and 26.5 hours a week for primary-school teachers. This is in fact not too much but Japanese teachers also have a lot of supplementary tasks. For example, high- and middle-school teachers are often required to give additional lessons in which students are prepared for the 'examination hell' (the flood of entrance examinations to higher-level schools or universities) or to supervise students’ club-activities which take place in the afternoon (cf.

OKANO/TSUCHIYA 1999, p.151-152). Another difference, compared to Western countries, is the excessive number of students per class. Teachers often face more than 35 in primary and middle school and they have to teach very heterogeneous classes (according to the students’ abilities) because of the missing separation at Japanese schools.

Probably the strangest tasks (in the eyes of Western teachers) are things like guarding the campus and ordering the fuel oil. They are also partly responsible for their students outside school. Japanese students have to follow several rules in their leisure time: they are not allowed to smoke and to drink alcohol, to go to discos or to have a job by the side. In case of disregarding these rules, the teacher is obliged to inform the parents or even to make home visits (cf.

SCHÜMER 1999, p. 34). As one can see from all this, the tasks of a Japanese teacher go far beyond giving lessons. It should be stressed that the situation for female teachers is even more strenuous because they are also responsible for housework and bringing up the children at home (as this has consequently remained the task of women in the Japanese society).

As already mentioned, Japanese students are not rated according to their abilities. They remain together with all the other children of their age and are moved up jointly, independ-ent of their achievement levels. This system, that is fairly unknown in Western societies, stops abruptly when compulsory education ends at the age of 15. From this point onwards, the students must face masses of tests and entrance examinations to pass all barriers on the way to a reputable high school. The better the reputation of the attended high school, the bigger the chances to attend a reputable university afterwards (cf.

SCHUBERT 1997, p. 400). Therefore the parents enable their children to receive additional lessons where they repeat and consolidate their subjects. Normal school only prepares the students up to a certain point, so that they need these additional lessons, if they want to have any chance to pass the difficult entrance examinations. The focus of these additional schools (after-school schools,

“juku”) is on repeating and practising the subjects on the one hand and rote learn-ing on the other. Other schools focus on exam preparation. The students display persever-ance and intensity to a high degree which could hardly be imagined by Western students. This additional school system is unique and typical of the Japanese education where it plays an important role. It is designated as “shadow” school systems whereas the official school system comprises public and private schools (cf.

LEESTMA/WALBERG 1992, p. 239). To guarantee the best possible education, parents and children muster up great strain equally. In former times the slogan

“kyoiku no kanetsu” (overheating of education) was used in this context and the term of “examination hell” was created (cf.

WITTIG 1972, p.161).

Nevertheless teacher’s life in Japan can be pleasant compared with Western countries. The classes are usually homogeneous in terms of ethnicity so that no language problems occur. The relationship between teachers and students is characterized by mutual respect and teachers do not have any difficulties with lack of discipline. Although the general situation at Japanese schools is not as unscrupulous as it used to be (concerning violence, harass-ment, disrespectfulness), it can be regarded as insignificant measured with Western condi-tions. The teaching situation is relatively uncomplicated due to the children’s education at home. Japanese children learn to adapt themselves to groups very early so that they are more likely to accept goals, meaning and methods of schooling (cf.

SCHÜMER 1999, p. 35). The teacher’s authority is not scrutinized. In class, the students are able to work persever-ingly because of their high sense of performance of one’s duties. They know about the im-portance of exertion which will lead to social appreciation.

Teaching in Japan is seen as a kind of lifestyle guidance for the students. A teacher con-centrates not only on the cognitive development of children, but also on their emotional, social, physical and mental one (cf.

OKANO/TSUCHIYA 1999, p. 172). They let the children practise correct behaviour in school life and delegate more and more responsibility in course of time. The children are allocated different tasks: some are responsible for general behaviour towards the teacher in class (greeting, saying goodbye, quiet), some care for the served meals, and others see to a clean blackboard. In general, the authority of children being responsible for a certain task is accepted by all the others – although there are of course children who fulfil their jobs more sufficiently than others.

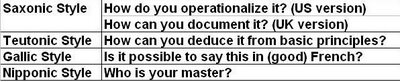

Download article as PDF (cf. GALTUNG 1985)

(cf. GALTUNG 1985)